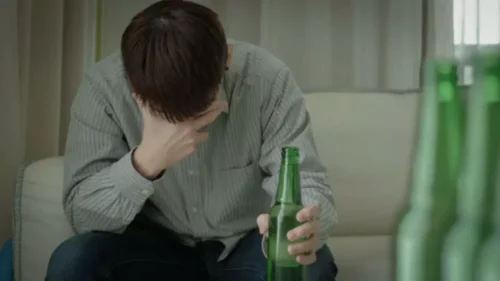

From Curiosity to Dependence: The 4 Stages of Alcohol Misuse

People who have a dependence on alcohol exhibit some or all of the following characteristics. This change was made to challenge the idea that abuse was a mild and early phase of the illness and dependence was a more severe manifestation. For example, we have long been told that people need to hit “rock bottom” before they’ll get help, but this isn’t true. Anyone with an addiction can get help at any point if they feel it’s the right time. Samantha Green, a psychology graduate from the University of Hertfordshire, has a keen interest in the fields of mental health, wellness, and lifestyle.

Long-Term Behavioral and Physiological Consequences of Early Drinking

Frequently, alcohol misuse does not occur in isolation but alongside other mental health disorders, a situation known as co-occurring disorders or dual diagnosis. Common co-occurring conditions include depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and PTSD. Treatment for alcohol dependence in such cases must address both the addiction and the mental health condition to ensure a holistic recovery. This dual approach helps prevent relapse and promotes a more stable, long-term recovery.

- This means they can be especially helpful to individuals at risk for relapse to drinking.

- Referring to this condition as alcohol use disorder is more accurate and less stigmatizing.

- Several terms including ‘alcoholism’, ‘alcohol addiction’, ‘alcohol abuse’ and ‘problem drinking’ have been used in the past to describe disorders related to alcohol consumption.

- Likewise, if drinking or using drugs with others provides relief from social isolation, substance use behavior could be negatively reinforced.

Coping and support

- Although not directly comparable because of different methodology, a low level of access to treatment is regarded as one in ten (Rush, 1990).

- People who are alcohol dependent are often unable to take care of their health during drinking periods and are at high risk of developing a wide range of health problems because of their drinking (Rehm et al., 2003).

- Most medical schools only devote a few hours over four years to teaching addiction medicine, a mere fraction of the time devoted to other chronic diseases encountered in general practice [8].

- The involvement of these reward and habit neurocircuits helps explain the intense desire for the substance (craving) and the compulsive substance seeking that occurs when actively or previously addicted individuals are exposed to alcohol and/or drug cues in their surroundings.

- The basal ganglia, a part of our brain involved in habit formation, strengthens the association between drinking and the context in which it occurs.

If the responding is extinguished in these animals (i.e., they cease to respond because they receive neither the alcohol-related cues nor alcohol), presentation of a discriminative cue that previously signaled alcohol availability will reinstate alcohol-seeking behavior. A growing body of substance use research conducted with humans is complementing the work in animals. For example, human studies have benefited greatly from the use of brain-imaging technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans.

Alcohol and the Brain

The AAF for alcoholic liver disease and alcohol poisoning is 1 (or 100% alcohol attributable) (WHO, 2000). For other diseases such as cancer and heart disease the AAF is less than 1 (that is, partly attributable to alcohol) or 0 (that is, not attributable to alcohol). Also, as noted earlier, the risk with increasing levels of alcohol consumption is different for different health disorders. Risk of a given level of alcohol consumption is also related to gender, body weight, nutritional status, concurrent use of a range of medications, mental health status, contextual factors and social deprivation, amongst other factors. Therefore it is impossible to define a level at which alcohol is universally without risk of harm.

Those with moderate to severe alcohol use disorders generally require outside help to stop drinking. This could include detoxification, medical treatment, professional rehab or counseling, and/or self-help group support. Alcohol abuse was defined as a condition in which a person continues to drink despite recurrent social, interpersonal, health, or legal problems as a result of their alcohol use.

There is therefore some further progress needed to make alcohol treatment accessible throughout England. Alcohol dependence is also a category of mental disorder in DSM–IV (APA, 1994), although the criteria are slightly different from those used by ICD–10. For example a strong desire or compulsion to use substances is not included in DSM–IV, whereas more criteria relate to harmful consequences of use. It should be noted that DSM is currently under revision, but the final version of DSM–V will not be published until 2013 (APA, 2010). Unlike tolerance, which focuses on how much of the substance you need to feel its effect, physical dependence happens when your body starts to rely on the drug.

Can Tech Transform Recovery? Exploring the Latest Innovations in Addiction Treatment

Current practice in treating AUD does not reflect the diversity of pharmacologic options that have potential to provide benefit, and guidance for clinicians is limited. Few medications are approved for treatment of AUD, and these have exhibited small and/or inconsistent effects in broad patient populations with diverse drinking patterns. The need for continued research into the treatment of this disease is evident in order to provide patients with more specific and effective options. This review describes the neurobiological mechanisms of AUD that are amenable to treatment and drug therapies that target pathophysiological conditions of AUD to reduce drinking. In addition, current literature on pharmacologic (both approved and non-approved) treatment options for AUD offered in the United States and elsewhere are reviewed.

Both acute and chronic heavy drinking can contribute to a wide range of social problems including domestic violence and marital breakdown, child abuse and neglect, absenteeism and job loss (Drummond, 1990; Head et al., 2002; Velleman & Orford, 1999). Some studies using animal models involving repeated withdrawals have demonstrated altered sensitivity to treatment with medications designed to quell sensitized withdrawal symptoms (Becker and Veatch 2002; Knapp et al. 2007; Overstreet et al. 2007; Sommer et al. 2008; Veatch and Becker 2005). Moreover, after receiving some of these medications, animals exhibited lower relapse vulnerability and/or a reduced amount consumed once drinking was (re)-initiated (Ciccocioppo et al. 2003; Finn et al. physiological dependence on alcohol 2007; Funk et al. 2007; Walker and Koob 2008). Indeed, clinical investigations similarly have reported that a history of multiple detoxifications can impact responsiveness to and efficacy of various pharmacotherapeutics used to manage alcohol dependence (Malcolm et al. 2000, 2002, 2007). Future studies should focus on elucidating neural mechanisms underlying sensitization of symptoms that contribute to a negative emotional state resulting from repeated withdrawal experience. Such studies will undoubtedly reveal important insights that spark development of new and more effective treatment strategies for relapse prevention as well as aid people in controlling alcohol consumption that too often spirals out of control to excessive levels.